Local environmentalists are ignoring the biggest opportunity to reduce emissions with local policy

This piece was originally published in Streetsblog on Oct 21.

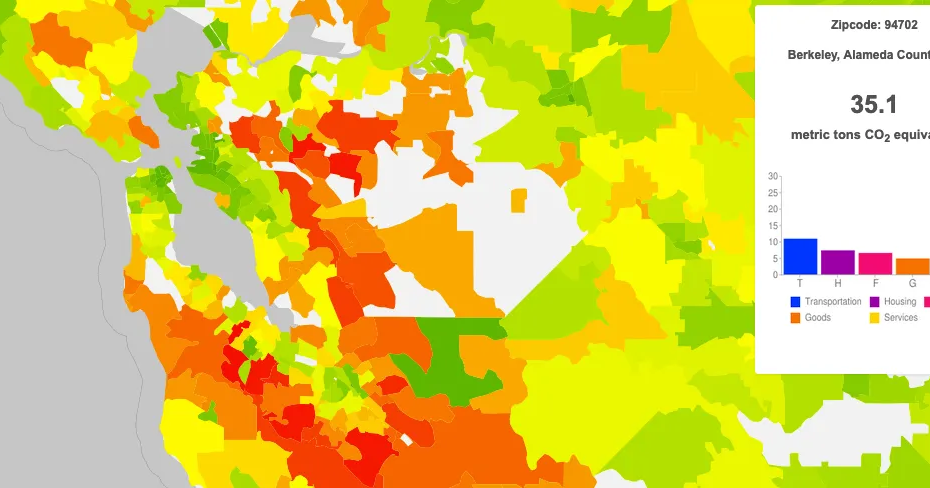

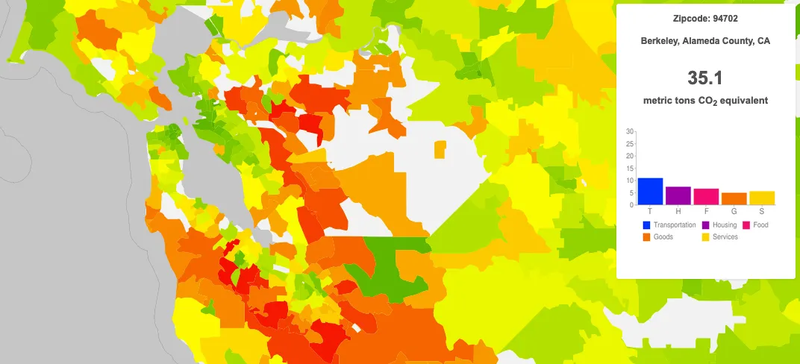

Average Annual Household Carbon Footprint by Zip Code (c/o Coolclimate)

Over the last several years, local environmental organizations and their endorsed candidates have ratcheted up ambitions for tackling the climate crisis. We are hearing overdue calls for getting fossil fuels out of our buildings, our cars, and our power grid. Advocates rightly demand that we halt new fossil fuel extraction and advance a just transition to a renewable economy. And in 2020 we are reminded that in the Bay Area, respect for science and expertise are broadly shared values in the face of threats to our way of life.

The same level of ambition is not shown for tackling our housing crisis. Instead, from many of the same candidates and organizations, we hear a litany of excuses for not taking the action that experts agree is needed: build more “infill” housing of all kinds in our existing communities to avoid further sprawl and displacement. Ending exclusionary zoning is now a consensus policy for national Democrats from Vice President Joe Biden to Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Leading urban planning scholars including the former head of the American Planning Association have called for eliminating single family zoning and related barriers to equitable land use outcomes.

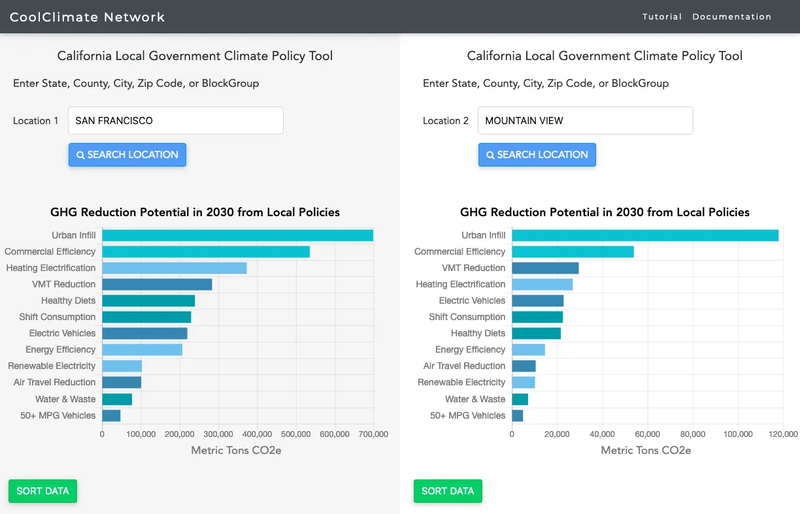

The link between climate and housing is abundantly clear. Simply allowing more people to live in Bay Area cities is one of the most potent means of reducing climate pollution with local policies, according to research led by UC Berkeley’s Chris Jones (available interactively at coolclimate.org): indeed, it could be the single most impactful measure for Bay Area cities ranging from San Francisco and Oakland to Mountain View. This is because cities in the inner Bay Area already have relatively low carbon footprints, particularly the transit-rich core. Housing we don’t build in cities ends up in outlying suburbs where driving is required for most daily activities, necessitating far more asphalt, steel, and concrete, and gobbling our forests and farmlands — not to mention exacerbating wildfire risks. A drumbeat of reports from Next 10, Energy Innovation, Transportation for America — and the state’s own Air Resources Board — have said that the continued upward trend in miles driven is a threat to our emissions goals, even considering a continued shift to electric cars.

Urban infill is the top measure for reducing 2030 emissions from local policy in the Coolclimate scenarios for San Francisco and Mountain View. (c/o Coolclimate)

Yet many local environmental organizations and their endorsed candidates ignore the issue or raise specious concerns about traffic and green space — missing the point that allowing more people to live in walkable neighborhoods will reduce traffic and give urban space to people and trees instead of cars. The most egregious example is the Sierra Club’s endorsement of Cupertino Mayor Steven Scharf, who fought housing in a long-vacant mall and notoriously joked about building a wall around the city to exclude commuters. Another deflection is the claim that market-rate housing will accelerate gentrification: a legitimate concern (though counter to initial research) in the communities of color and low income that have borne the brunt of displacement and disinvestment, who should be empowered to implement their preferred solutions. But when it comes to the string of exclusive locales that have been the direct economic beneficiaries of redlining and unfair housing laws, from Marin through SF’s Westside south to the Peninsula, the opposite is clear: legalizing apartments would help integrate neighborhoods and expand access to opportunity.

Why do we see this mismatch in priorities, when infill housing is the prime climate intervention squarely within the power of local governments? Perhaps given the state of our national politics, we have taken for granted a shallow approach to problem-solving, scapegoating instead of facing challenges head on. Taking on the fossil industry and calling for a just transition is bold and praiseworthy in Bakersfield. But in SF and Palo Alto there is no base of support for the fossil fuel industry; instead, there are wealthy, white homeowners who resist needed change and hoard their Prop 13-enhanced assets. It doesn’t help that many of these homeowners lead prominent environmental organizations and vote Democratic.

Because of this, when voting in local elections, rather than turning to environmental organizations, the best way to cast your ballot for climate solutions may be following your local pro-housing organization, such as YIMBY Action affiliates or East Bay for Everyone. Fortunately, throughout the Bay Area we do have many candidates with bold visions for addressing our housing and climate challenges and making our society more equitable: candidates like Danny Sauter and Marjan Philhour in SF, Amo Lee in San Mateo, Cari Templeton in Palo Alto, JR Fruen in Cupertino, Alysa Cisneros in Sunnyvale, and Jake Tonkel in San Jose. And of course Sen. Scott Wiener, who has been more outspoken on the need for land use reform than just about any American politician. And we won’t solve these generational problems in one election cycle: even after we bid 2020 adieu, we can use your ideas and your volunteer hours to help us build an inclusive, climate-resilient Bay Area.